“Vive le Québec huître!”

—Charles de Gaulle

|

|

The Oyster Foundation’s Third Annual Meeting: in Montreal

We were 16 strong on Sunday, July 4th, 2004, including new members Dick O’Hagan of Toronto, Jethro Marks of Ottawa and Anna Berenfeld of New York and London.

We met at 3 p.m. on the ground floor of Auberge

Le Saint-Gabriel in Old Montreal,

the oldest inn in North America,

for presentation of the Oyster papers, along with champagne and canapés.

In this, the third year of our existence, we introduced poetry and music

to the mix. After we sang “O

Bienvenu au

Richard O’Hagan

Stephen,

fellow Oysterians: thank you for including me in your very special company

on this Fourth of July. Even before meeting you, I was made to feel welcome

by the warmth of the messages I received. They seemed to me a courtesy

of exceptional grace and thoughtfulness. I appreciated them very much.

Stephen,

fellow Oysterians: thank you for including me in your very special company

on this Fourth of July. Even before meeting you, I was made to feel welcome

by the warmth of the messages I received. They seemed to me a courtesy

of exceptional grace and thoughtfulness. I appreciated them very much.

You will each be making your own discoveries here in Montreal. I made mine even before arriving. It was this: getting to know Stephen Banker as gourmet and social convener-cum-tour manager; an altogether new dimension to me. It is reassuring that his originality of mind and breadth of interests are as active as ever.

Place and time prompt me to recall an earlier example of Banker’s hosting talent. We’re going back many years to Washington, D.C. when Stephen introduced me to a Canadian athlete whose name may be familiar to some of you — Ken Dryden. He was the All-Star goaltender for the legendary professional hockey team from this very city — Les Canadiens. Dryden was in Washington as a Nader’s Raider, a fact I learned to my embarrassment at Stephen and Susan’s home. There I was, the head of information at the Canadian embassy, not even knowing the superstar was in town, invited to make his acquaintance over supper along with the South African tennis player, Cliff Drysdale, by our protean leader, no slouch on the courts himself. But it was Dryden’s presence that engaged me.

A prodigy

as schoolboy athlete, he had gone to Cornell and become an intercollegiate

standout, and from there to the National Hockey League and even greater

glory — the most valuable player in the Stanley Cup playoffs in his rookie

year. But he was more than a gifted athlete, as the Chief Oysterian had

already discerned. Ken Dryden was talent compounded, the full shape of

which had yet to show itself. But we know now: lawyer; best selling author,

including a classic on hockey; a public servant and advocate of special

causes; most recently president of the Toronto Maple Leafs hockey club

and as of June 28 when a federal election was held, Member of Parliament

(and now a Cabinet Minister) of the governing Liberal Party. That long

ago supper on a muggy night in D.C. was of course the merest foreshadowing

of our present séance where I find myself facing not one but a whole of

host of luminaries — again at the inspired instance of our leader. Stephen,

I salute you.

A prodigy

as schoolboy athlete, he had gone to Cornell and become an intercollegiate

standout, and from there to the National Hockey League and even greater

glory — the most valuable player in the Stanley Cup playoffs in his rookie

year. But he was more than a gifted athlete, as the Chief Oysterian had

already discerned. Ken Dryden was talent compounded, the full shape of

which had yet to show itself. But we know now: lawyer; best selling author,

including a classic on hockey; a public servant and advocate of special

causes; most recently president of the Toronto Maple Leafs hockey club

and as of June 28 when a federal election was held, Member of Parliament

(and now a Cabinet Minister) of the governing Liberal Party. That long

ago supper on a muggy night in D.C. was of course the merest foreshadowing

of our present séance where I find myself facing not one but a whole of

host of luminaries — again at the inspired instance of our leader. Stephen,

I salute you.

I hope it won’t seem presumptuous of me to extend to all of you a warm welcome, bienvenue, to this historic and prized Canadian city. It’s where I, like Ken Dryden, spent several contented and stimulating years of professional life.

For a very long time, Montreal was

I alluded to the recent election. The Liberal party, to which I have devoted

much of my career, has been in power for the past ten years and has been

our dominant party for a hundred years, was returned to office, but with

a minority in the House of Commons. It is our first minority government

in 25 years. This one is of more than ordinary interest because of the

realignments produced and their regional sources. Regionalism is a reality

of political life in

Because of the issues playing in and out of this mix, a francophone separatist

party, the Bloc Quebecois, emerged with the third largest number of seats

and a grip on the balance of power. That in itself is at least ironic

since the Bloc Quebecois is dedicated to extracting Quebec

from

Let me conclude with a word on the vexatious subject of Canadian identity. You know the facts — that we are one of the world’s most advanced economies, are bifurcated linguistically, and talk endlessly about our constitution. In the National Review, John O’Sullivan called our politics “excessively exciting”. But that would be overstating it, even in wryness.

Michael Kinsley once ran a contest in the New

Republic on the most boring

newspaper headline imaginable. The New York Times won with “Worthwhile

Canadian Initiative.” References to

When we obsess

over our image and what others think of us, it is really the

When we obsess

over our image and what others think of us, it is really the

Other prime

ministers haven’t fared so well. I think back to 1965 and the US-Canada

Auto-Pact, forerunner of the North American Free Trade Agreement, NAFTA.

Our Prime Minister then was Mike Pearson, an affable, easily met man if

there ever was one, and a genuine star of the international arena — one

of the architects and builders of the UN and a Nobel prize winner over

Suez. I accompanied him to LBJ’s Texas

ranch for the signing. Maybe it was the sober garb — dark suit and vest

— but when Mr. Pearson stepped out of his jet, the President, in ranch

tans, opened wide his arms and expansively welcomed, for the benefit of

the assembled press, “Prime Minister Harold Wilson.” Mr. Wilson was British

Prime Minister at the time. Pearson never batted an eye.

Other prime

ministers haven’t fared so well. I think back to 1965 and the US-Canada

Auto-Pact, forerunner of the North American Free Trade Agreement, NAFTA.

Our Prime Minister then was Mike Pearson, an affable, easily met man if

there ever was one, and a genuine star of the international arena — one

of the architects and builders of the UN and a Nobel prize winner over

Suez. I accompanied him to LBJ’s Texas

ranch for the signing. Maybe it was the sober garb — dark suit and vest

— but when Mr. Pearson stepped out of his jet, the President, in ranch

tans, opened wide his arms and expansively welcomed, for the benefit of

the assembled press, “Prime Minister Harold Wilson.” Mr. Wilson was British

Prime Minister at the time. Pearson never batted an eye.

Fast forward to 2004 and the G8 summit in

And then there was the Reagan funeral. Along with Margaret Thatcher, Brian Mulroney, a former Canadian Prime Minister, was invited to eulogize the late president — an undoubted honour — which he did with some panache. Mulroney, a champion schmoozer himself, and the Great Communicator had hit it off so famously that at a summit in Quebec City they joined up before a black-tie audience to warble When Irish Eyes Are Smiling. Following the funeral, Brian reminisced about the friendship with Larry King on CNN. At the end, King thanked Mulroney for coming on his show, “Great seeing you again.” “Great to see you, Larry,” replied Mulroney “thank you for having me.” With that, King sent Mulroney on his way, remarking amiably to his audience: “Good guy! Brian Mulroney, the former Prime Minister of Great Britain.”

Chances are they all would have gotten the name right had the charismatic Pierre

Elliott Trudeau been their guest. And if he had been, he might well have

taken the opportunity to tell them that the true richness of

As I learned over my years in his administration, Trudeau saw the development

of democratic federalism and pluralism as matters of urgency for world

peace and the success of new states. He called

I profoundly hope he is proved right. And if he is, it may yet fix our identity

problem — even in the

After a refreshing round of bubbly and nibblies, Marty Moleski stepped forward. I had encouraged him to write the best, most powerful piece he could, but at the same time I had a lingering thought that some people would resent having a morbid subject presented at what was supposed to be a celebratory gathering. However, Marty’s inherent charm, his intensity and his speaking skills made the theme all the more compelling, framed by compassion.

A Bitter Cup

Martin X. Moleski, SJ

Hi, everybody. My name is Marty Moleski, and I'm an alcoholic.

Hi, everybody. My name is Marty Moleski, and I'm an alcoholic.

I recognized this fact pretty much by accident on April 24, 1981, between 3:30 and 4:30 in the afternoon. It was two months before my ordination to the priesthood. I was trying to help one of my lay friends, Brian, who was in the habit of getting drunk and getting arrested. Brian played guitar in my folk group. We had worked in the same community for the handicapped and we had a lot of feelings in common for the people we had worked with.

Both Brian and I were on student visas at the University of Toronto. I was

afraid that his arrests would cause him to be expelled from

When the theory of setting a rational limit didn't work, I decided to try rescuing him. I volunteered to pick up his car when he got drunk. A few days after I made the offer, he called from a bar on Spadina Avenue to report that he was getting drunk. He was celebrating the fact that he'd gotten his driver’s license back that day. I took the trolley downtown, had a beer or two with him and his friends, then drove his car back to my house. Brian stayed in the bar to continue the celebration.

The next morning, the car was gone. Brian had gotten arrested for walking while intoxicated, and spent a few hours in the drunk tank. Then he came back to my place, still drunk, and used a key he kept under the hood to drive himself home. For me, this was the last straw. I realized that he was a hopeless alcoholic, and I set up an appointment with him to read him the riot act.

As the song says in Man of La Mancha, I was only thinking of him—I was only thinking of him, but my drinking bothered me, too.

I went into the parlor that afternoon armed with materials to prove to Brian that he was an alcoholic. I had a diagnostic quiz with twenty questions. Among them:

Do you feel guilty about drinking? Yes.

Do you drink to deal with your feelings? Yes.

Have you tried to control your drinking? Yes.

Do you drink alone? Yes.

Is there unhappiness in your family due

to drinking? Yes.

Do you associate with inferior companions

when you are drinking? Yes.

Have you lost time from work due to drinking? Yes.

These were my Yes answers. It only takes three Yes answers to pass the test, and I had seven.

Brian was much worse, I thought, because he had arrests on his record, and he had many friends like me who told him that he was in trouble.

When I had first taken the test, I was shocked to learn that I had passed the test but I didn't feel guilty enough to stop drinking altogether. I mentally modified all of my answers. Yes, I drank alone when I was cooking for the community, but the unhappiness in my family was due to Dad's drinking, not mine, and all the so-called inferior companions with whom I drank were my fellow Jesuits.

Although I obliterated the responses from my mind, I neglected to erase the pencil marks I had made on the quiz sheet. When I started to give Brian the test, he noticed them and asked whose answers they were. I admitted that they were mine. He said, "Then that proves that you are an alcoholic."

He had me. With him looking over my shoulder, I had to admit that I had passed a test that I wanted desperately to fail. My life changed that day. Brian's didn't.

I took out my favorite Bible and wrote on the flyleaf: "I am an alcoholic. I choose not to drink." After I had signed and dated this confession, I felt a surge of despair. I reopened the Bible and wrote: "P.S. Please help me, God."

I had made a commitment to sobriety. The promise was in front of my eyes every time I opened the Bible, to say nothing of God’s eyes.

But keeping the vow was not easy. It took five or six years for me to join the fellowship of recovering alcoholics. Time after time, I fell into depression. ... The religious convictions that led me into the Society of Jesus and the priesthood helped, I guess, but I had been building on sand for many years while living under the influence of my own alcoholism.

After seven or eight years, my life in sobriety gained stability. I thought I understood the nature of alcoholism and of recovery. Much of my life, including my professional life — my priestly duty — was constant. But the learning process had not ended.

In the Spring of 2002, I was on sabbatical in a Jesuit

community in Chicago. It was a small

house. It's always hard for an ongoing community to absorb temporary

outsiders. My presence changed the dynamic in countless ways. I would

read in the library in the morning and afternoon, then watch TV in the

basement in the evening hours. I dimly realized that I was ruffling the

feathers of Michael Madubuko, a Jesuit priest from

Michael was a small man with a big smile. His hair was close-cropped, and he looked like royalty in his orange or purple dashiki. He liked to watch TV lying on the same sofa that I had chosen for myself. Sometimes he would get to the TV room first, other times I would. We had a long theological argument in a restaurant in March, the kind of debate that I thoroughly enjoy—passionate, wide-ranging, and very challenging. I appreciated his willingness to confront me and felt that we were good friends in spite of our different worldviews.

Early in April, after I'd been in the house for a couple of months, I noticed that Michael had disappeared from evening meals and no longer was competing for control of the TV room. I asked where he had gone. Folks said, "That's Michael. He doesn't like our food very much. Sometimes he withdraws for a while."

Early one morning, after I hadn’t seen him for several days, he knocked on my door, waking me up. When I opened the door, there was Michael, jabbering incoherently and waving a cigar humidifier at me. He handed it to me, then came back a few minutes later with a ragged Cuban cigar. I didn't know what to make of the entire dialogue, such as it was. I did smoke the cigar later in the day, sitting in the weak spring sunshine, and I still use the humidifier in my humidor.

Later that day, I expressed my concern to others in the community over Michael's condition. I found out that he had been treated for alcoholism some years earlier and that he had gone on several benders in the last month.

I knew the right thing to do. When a man relapses after treatment, he needs to go through treatment again. I called the police in desperation at one point, but they refused our request to come help us get him into a rehab. So we made plans to take Michael to Guest House in Rochester, Minnesota, a facility that specializes in the care of alcoholic priests. Michael was just 37 years old and seemed vigorous, so we all felt he would weather this storm as he had others in the past.

It took five hours for the head of the house, Father Bob Bueter, and me to talk Michael into returning to treatment. When we started the argument that morning, Michael was drunk and disoriented. Late in the afternoon, he agreed to pack his bags. Michael stumbled as we were walking downstairs, and I caught him. With some difficulty, we finally got him in the car for the seven hour ride to Minnesota. He fell asleep before we reached the expressway out of Chicago. This was a great relief to Bob and me.

Michael stirred a few times and drank some water en route, but refused the Big Mac and fries that I bought him for dinner. I ate them myself after they had gone cold. Michael pushed his seat back and put his bare feet up on the dashboard after asking Bob if that was OK. We figured it was good for him to sleep off his most recent binge, and we were grateful that the long debate with him was over.

When we arrived at Guest House, it was cold and dark. I opened Michael's door and started tying on his shoes for him, but he didn't stir. Only after I got his shoes on did I turn and notice that his eyes were open, staring off into the darkness. I tried to slap him awake, but there was no reaction. Then he stopped breathing. I gave him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, and he began to breathe again, though not for long. I kept on trying, but he never breathed on his own again. The emergency workers went through all the procedures required in such cases, but I could tell from the first time they looked at him that they had no hope for him whatsoever.

Michael's liver had failed. He was a dead man walking when we started urging him to accept treatment that morning. For Bob and me, it was a long trip back to Chicago.

Some of Michael's Nigerian friends were outraged when they learned how Michael had died. Bob and I met with twenty of them a few nights after his death. They accused us of racial hostility. "If Michael had been a white man, he would not have died." I lost my temper after two hours of inquisition and yelled at them, "Why do you think we were in the car with him? Don't you understand that we loved him and wanted what was best for him?" The meeting ended very shortly afterward.

I could not admit it to myself or to them that night, but they were right. When a white man suffers liver failure, his skin turns yellow, and anyone can see that he is in a crisis. Michael was a very black black man, and I did not know until he died that when a black man suffers liver failure, his skin turns grey. I had looked at Michael's grey feet all afternoon, up on the dashboard, and not once had I realized that I was seeing the sign of his approaching death. Michael's African friends were right: if he had been a white man, he would not have died in the car at the doorway of the treatment center.

+ + + + +

Over the years, I lost touch with Brian. So far as I know, he is still drinking. Yet I thank him for the role he played in helping me confront my alcoholism. When I remember Michael, I mourn his death and feel the anguish of having failed him. Both of them were unwitting messengers, and even as they fell into darkness, they brought light to me.

The Psalmist says that the Lord has given us bread to make us strong, oil to make our faces shine, and wine to make our hearts glad. For those of you who can enjoy the pleasant effects of alcohol, I hope it makes your heart glad this evening. I love the Jewish custom of raising one's glass to life. I won't be able to drink what you are drinking, but I will join you in the spirit of the toasts and in the joy of The Oyster Foundation. L'chaim—to life!

At that point, Joe Schildkraut stood to say how touched he was by Marty’s presentation and how grateful he was to Marty for sharing it with us. As I look back, it seems to me that Joe’s deeply-felt remarks were part of the experience of Marty’s paper. We moved on. Time for refreshments (each to his own), and then I read my poem about Joseph H. Hirshhorn. I started with a few words of introduction for those who didn’t know much about the subject.

I'm going to read a poem today. It’s about, and spoken in the voice

of, Joseph H. Hirshhorn, whose lasting memorial is the Hirshhorn

Museum & Sculpture Garden

in Washington. Joe Hirshhorn

was born in 1899 in

In 1915 when he was just 16, having followed the trade for four years, he jumped in with his newsboy savings and earned $168,000 the first year. Clearly, he had a knack. His success continued, and so did his uncanny sense of the market, and he cashed out with $4 million two months before the 1929 crash.

What next? Joe Hirshhorn looked north to

In the mid 1960s, he went to the town of Blind River, Ontario, near one of his richest uranium strikes, and said, “I’d like to give you $100 million worth of art. This place will be a Mecca for art lovers all over the world. And all I ask is that you change the name from Blind River to Hirshhorn, Ontario.”

Blind River refused. So he went to Ottawa and made the same offer, requesting only that the name of the national museum be changed. Again he met with refusal, perhaps a function of Canadian pride and reserve. But then the Smithsonian Institution — we Americans know a deal when we see it — offered to build him a museum on the Washington Mall. In 1974, the Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden opened. It is, as you will hear Joe boast in a moment, one of only four monuments to individuals on the Mall — a 20th century refugee, along with the founders of the country.

Joe died in 1981. The museum remains a focal point for contemporary art. If you visit it, you will be struck, I think, by two themes — first, the loudness of the colors, the primary hues that so excited and attracted him; and second, the unpredictability of the shapes: even the picture frames are not consistently rectangular, and the sculpture is often surreal.

So when I wrote this poem, I decided to represent the bright colors with strong, heavy rhymes and to suggest the uneven shapes by constantly breaking the meter.

There is a disparaging reference in the poem to the National Gallery of Art, which was of course funded by the Mellon family. Joe hated it. He thought the Mellons had no taste in art, except for what they saw in Life Magazine and other arbiters of popular culture. He said that’s why it’s not called the Mellon Museum, because it doesn’t represent their taste. How could it? They had no taste! In the poem, as you’ll hear, when he says Mellon’s grandchildren are looking for a sign, he doesn’t mean some sort of cosmic beacon, he simply means a placard that identifies the donors — just like the one in front of his place.

I knew Joe Hirshhorn a little. I made a movie about him for the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. and conducted several interviews for CBC radio. It turned out he and his wife Olga shared a pew in the Greenwich, Conn. synagogue with my uncle and aunt. He was happy to chat with me, on air or off, and a great deal — an astonishing amount — of the poem you’re about to hear is actually what he said. For example, the fact that there are 5 aitches in his name. He took some pride in that. There’s a collector for you!

*******

THE DEVIL ON THE WALL

For Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1899-1981

Stephen Banker

“Mal nisht den Teifel an die

Wand”*

(*Yiddish proverb: “Don’t draw the devil on the wall,” or “Keep

your darkest thoughts to yourself.”)

*

I, Joseph H. Hirshhorn, with five

aitches, born

on the other side, made a name up north,

a kid out of Mitau who came to adorn

this country's capital, of monuments the fourth —

Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln and me — it's official,

and not a one of them with a middle initial.

A Latvian child in a Brooklyn

flat

already marked as late to arrive,

a greenhorn newsboy chasing daily wages,

a shrimp in a businessman’s hat,

I sat on the curb and ripped the pages

of Colliers, SatEvePost, and Barbershop Gazette

with color plates and evocation, to use a fancy word,

of something more — faces, pears and apples, mountains — that stirred

my juices, straightened my spine.

How could a shiny sheet of paper drive

me nuts for something not quite mine?

Not yet.

This whole collection I gathered

on my own —

I bargain, barter, bundle, beg and steal —

for when I see unlikely colors or hidden lines in stone,

everything goes still in me, there's a hush,

my skin is tight and my blood begins to rush.

First the silence, then a heavy roar

like the train outside the door

when I was small

until I don’t know longing from the real,

and then I pester everyone: I want, I want.

Go tell it to the wall, my mother cried, Geh red zu die Wand,

and that is what I've done. Look! Can you deny it?

Take it from a trader who can smell a deal:

Let your children hear your wisdom and apply it.

Say, don’t you like this better

than the National down the Mall

whose dried-up Mellons shied away from fame

with gifts that ran from certified to quaint?

Their lofty contributions were a waste

for grandkids looking for a sign.

But here, your hands, your eyes are mine.

This is my collection and my taste.

I throbbed for every pebble, every fleck of paint.

That’s why it bears my name.

If I had never turned uranium

into gold —

suppose I'd led a simple life, grown old

with nothing in my attic but the bags —

where would this need have gone, how to express

the yearning force, the fury to possess

some canvasses your experts thought were rags?

It would have been the same, the same.

I’d pile up things that just don’t cost:

Calendars. Clippings. Pictures of pictures. Maybe prints.

A worn-out copy of a piece that hints

at more than faded hues and tattered frame.

The difference is that this place has my name embossed.

It started when a child was taunted,

a misfit, driven, scared and small,

he hoarded drawings from discarded magazines,

then gathered paintings, sculpture, monumental scenes,

and told them to the wall, like Mama wanted.

©2004 Stephen Banker

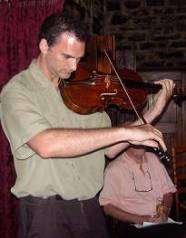

That broke the mood. And I sensed that people appreciated the poetry. Anyway, they laughed at the right places. The final contributor was Jethro Marks, a protégé of Pinchas Zukerman who is one of the outstanding musicians of his generation. At 6’ 6”, he cradles the viola as if it were a violin. He apologized for returning to a somber theme, for he had selected a piece called “Lamentations of Jeremiah” by the Canadian composer, Milton Barnes.

|

|

|

When Jethro finished, there was a long, appreciative pause before

the applause started. This performance was unlike anything The Oyster

Foundation had experienced. As I watched the reaction, I thought of Jethro’s

grandfather, Ed, whose writing about a junket to

Then I pointed out that all our meetings are strongly regional. Dick’s

talk, of course, was specifically about

But first we had to see the town. Four calèches (horse and buggies) awaited us for a tour of Vieux Montréal. I climbed aboard with Dick, Jethro and Anna. When the driver pointed out the home office of the Bank of Montreal, Dick modestly neglected to mention that he had been a vice president of that institution.

We returned to our hotels at about 6. That gave us an hour and a half to rest up and struggle into our formal clothes. Jethro and Anna, our energetic juveniles, elected to take a walk and quickly disappeared. I poked around for a while, napped briefly, and gave myself half an hour to don my tux, insert the studs and cufflinks and tie the bowtie. Since I was sharing my quarters with Jethro, and he still wasn’t back, I wondered if he would have enough time to put on his tuxedo. At 7:20 he flashed in, ironed his shirt, and slipped into his black tie, passing me on the outside track. Of course! The kid wears a tux every night.

Marty wore a special ruffled dickey, which for priests, so he says, is more formal than the flat kind.

We reassembled, all duded up (with a couple of exceptions), at 7:30 at St. Gabe’s upstairs salon privé. Betsy led us in a lusty July 4th rendition of “

Napoléon of Anna potatoes, cream of Vodka and green lemon, marinated salmon shaped as a rose.

Cold soup: Cappucino of carrot, ginger and lime

Foie gras poélé, salsa of exotic fruits, glazed with maple

WINE: Pinot Blanc, 2002, family estate, Okanagan Valley, BC

Rack of Boileau Deer, Geniper berries, jelly of green fir sap

WINE: Mission Hill 2001, Merlot, BC

Assortment of Quebec cheeses, (goat, blue, crème de la crème), sprouts of baby “cressonette fontaine”

Déclinaison of L’Ile d’Orléans strawberries

WINE: “Ice Wine”: Konzelmann Estate Winery, Niagara Peninsula, Ontario, VQA

How do you attach those little Quebec pins to the Oyster medallion?

Easy!

Everything you need to know is

on the license plate

Québec: La Belle Province — Je me souviens!

Compiled

and edited by Stephen Banker

Additional photography by

Boris Berenfeld

HTML version by Martin X.

Moleski, SJ